2. WHAT IS LEISURE?

At first glance the concept of “leisure” – comprising

social, recreational, and entertainment

activities – is apparently well-understood. Numerous scholars have

noted, however, that

defining leisure is not at all as straightforward as might be initially

assumed (see, e.g., Howe and Rancourt, 1990). This section first reviews

and critiques several definitions of leisure. It then points to one

key source of difficulty in defining it – the fact that the boundaries

between leisure and other types of activities are not crisp – and

discusses three ways in which this is true. One means of further defining

an object is to classify the various forms in which it can be manifested,

and also in this section we review several classification schemes for

leisure activities that have been previously offered.

2.1 Definitions of Leisure

The literature contains a number of definitions of leisure. For example,

the 130 Australian

adolescents studied by Passmore and French (2001) indicated that freedom

of choice and

enjoyability were crucial to an activity being considered leisure. Similarly,

Tinsley, et al. (1993, p. 447) define four necessary characteristics

for a leisure experience to occur: “The individual must perceive

the activity as (a) freely chosen, (b) intrinsically satisfying, (c)

optimally arousing, and (d) requiring a sense of commitment.” But

clearly at least the latter three characteristics can apply to subsistence

and maintenance activities as well as leisure, and even the first characteristic,

freedom of choice, can apply to numerous tasks within an individual’s

job or to certain aspects of maintenance activities. Conversely, it

seems rather strict not to consider an activity such as accompanying

a spouse to a ball game to be leisure if the individual does not entirely

freely choose it, or is not fully “committed” to it or “aroused”

by it (see, e.g., Kelly, 1978).

Meurs and Kalfs (2000, p. 128) define “leisure time” as “all

the time a person does not devote to ensuring their [sic] future welfare

in a broad sense.” They indicate that this definition thus

excludes activities associated with generating income, running a household,

and maintaining

physical well-being. They further define “leisure travel”

as “all journeys not specifically made with the purpose of providing

for the person’s future welfare or even for sustaining a normal

life.” In other words, “there is no future penalty for not

making these journeys.” Yet these definitions also seem restrictive.

Leisure activities should certainly be considered essential to one’s

psychological welfare, i.e. welfare “in a broad sense”, with

a corresponding psychological penalty for their complete neglect. And

the exclusion of activities that support physical wellbeing would eliminate

a large category of recreational activities, such as participatory sports

or exercise, that would normally be classified as leisure.

Interestingly, although they can be more readily deferred or “compressed”

than can subsistence or maintenance activities, leisure activities are

seemingly less readily transferred than the other two types.4

Work and maintenance activities are considered essential to the individual’s

physical well-being (although these activities can also make an important

contribution to one’s psychological well-being). As such, an individual

can receive similar physical benefits from outsourcing many 5

of the latter two types of activities to other individuals (e.g. by

marrying a person who supports the household financially, or by hiring

domestic help). In contrast, since the main contribution of leisure

activities is to psychological well-being (although recreational activities

can also support the physical dimension, as mentioned above), the individual

does not benefit by outsourcing leisure to others 6. Thus,

ironically, it is more essential to our well-being that we personally

engage in leisure activities than that we personally engage in mandatory

or maintenance activities.

One reason for the nebulous nature of the concept of leisure is that

the boundaries between

leisure, mandatory, and maintenance activities can be quite permeable.

This permeability occurs in three different ways – the first conceptually

intrinsic to how the individual perceives an activity, the second largely

facilitated by ICT, and the third often but not exclusively associated

with ICT.

2.1.1 Permeable Boundaries (1): One Activity, Multiple Aspects

The first basis for the permeable boundaries between activity types

is that intrinsically, many

activities possess characteristics of more than one of the conventional

three categories (G`tz, et al., 2002; Meurs and Kalfs, 2000; Shaw,

1985; Tinsley, et al., 1993). This can be for a

combination of three different reasons: (1) The same activity may

be experienced differently by different people; (2) the same activity

may be experienced differently by the same person at

different times; and (3) an activity for a single person at a single

time may mix aspects of

multiple categories.

Examples of the general principle come readily to mind: eating out

or even cooking could be

considered maintenance activities, but are forms of recreation for

many people. The same can be said of gardening and even housework

or home repairs and improvements. Child care can be quite entertaining

under the right circumstances (Shaw, 1984). Work-related travel and

even commuting have some discretionary aspects for many (Mokhtarian

et al., 2001; Redmond and Mokhtarian, 2001; Ory, et al., 2004). Hochschild

(1997) points out that for many people, in contrast to the stereotype

of the dog-eat-dog work world from which home is a serene refuge,

work (where we interact with mature professionals who value our contributions)

is a welcome escape from home (where we interact with needy and demanding

family members). Howe and Rancourt (1990, p. 398) note that “[a]

generally accepted theme of the psychology of leisure literature is

that some people do find personal meaning and do experience freedom

and leisure in work.” 7 And the recreational/ entertainment

qualities of shopping (again, for some people) are well-recognized

(Salomon and Koppelman, 1988; Tauber, 1972) 8. Even

within the leisure category itself, an activity may have multiple

characteristics. When one goes to a ball game with friends, is the

activity social, or entertainment? The answer probably affects the

activity choice process, including the choice set of perceived alternatives:

if the primary motivation is social, one may first decide to get together

with friends, and then choose an activity around which to organize

the gathering, whereas if the primary motivation is entertainment,

one may first decide to attend the ball game and then see who else

is able to join.

This discussion speaks to the types and degrees of various motivations

for undertaking a given

activity, which may differ from what the activity “label”

itself would stereotypically imply (e.g. work is a necessary evil;

leisure is an optional good). Understanding those motivations is

important for analyzing the leisure activity engagement decision process,

and the role of ICT in that process. For example, Handy and Yantis

(1997) hypothesize that the more chore-like the activity (i.e. the

less that a mandatory or maintenance activity is viewed as having

leisure

overtones), the greater the likelihood of in-home substitution for

the out-of-home version of that activity.On the other hand, we are

wary of endowing a mandatory or maintenance activity with leisure

qualities simply because it can be pleasant. Meurs and Kalfs (2000)

consider enjoyment to be an important element of the definition of

leisure time, and it is tempting to equate enjoyment with leisure,

suggesting that to the extent that mandatory or maintenance activities

are enjoyed, they contain elements of leisure. But that may confuse

the concepts of “positive utility” and leisure: a job can

be enjoyable, stimulating, or fulfilling without being “leisurely”9.

Conversely, not all leisure activities may be enjoyable: one may visit

relatives but be miserable the entire time, or one may go to a gym

in order to stay physically fit but consider it “torture”.

We could say that a given activity constitutes leisure to people for

whom it is enjoyable (see, e.g., the brief review of literature on

“leisure as a state of mind” in Howe and Rancourt, 1990),

whereas to those for whom it is not, it constitutes a form of maintenance

– whether physical maintenance in the case of the gym, or social

maintenance in the case of visiting family out of duty. But relying

on subjective motivations as the basis for classifying the same activity

differently for different people is not very practical for the large

scale data collection and analysis needed for regional travel and

activity modeling (although it may well be appropriate for more exploratory

studies of activity and travel behavior, and as we discuss below,

it is relevant for understanding activity choices in general and modeling

ICT impacts on leisure travel in particular).

2.1.2 Permeable Boundaries (2): Multiple Types of Activities Fragmented

and Sequentially Interleaved

Second, the boundaries between activity types are blurry due to what

Couclelis (2000) refers to as the increasing fragmentation of activities,

generally made possible by ICT. Whereas before, work, shopping, and

leisure activities took place more or less in undivided blocks of

time at specialized locations, we now see such activities broken into

smaller chunks, interspersed with fragments of other activities, and

spread across a larger number of locations. For example, we shop from

the Internet or play computer games during a break at the office,

and work from home in the evenings (perhaps interwoven with family

interaction activities). We send and answer email while on vacation,

and engage in sightseeing activities while on business trips (e.g.,

ECMT, 2000 points to the rise in “business tourism”)

10. This increasing fragmentability is also expected to have

impacts on activity selection and scheduling, and the associated travel.

For example, one may choose to watch a movie on DVD rather than in

the theater precisely because the DVD can be stopped and started at

will, and therefore woven into other activities at home rather than

requiring the commitment of a larger block of time and a separate

trip (although the travel involved in acquiring the DVD must still

be taken into account, at least until downloading movies on demand

becomes more widespread).

2.1.3 Permeable Boundaries (3): Multiple Types of Activities Simultaneously

Overlapped

(Multitasking)

The third way in which boundaries between activity types are porous

is simply due to

multitasking, a case in which fragments of multiple activities of

different kinds actually

overlap 11. One may watch television (leisure) while

doing a routine work task (mandatory) at home in the evening, or while

cooking dinner (maintenance). One may phone a friend while

traveling home from work, make work-related calls while watching one’s

child play soccer, or receive a call while eating with family or friends.

Here again, the ability to multitask may affect one’s choice

of activity mode, location, and timing.

2.1.4 Implications

The blurry boundaries between various leisure activities and between

leisure and non-leisure

activities raise methodological complications. We have previously

mentioned the impracticality of classifying the same activity as leisure

or maintenance depending on one’s motivation for undertaking

it or enjoyment of it. Data collection and analysis are also inherently

complicated by the presence of fragmentation and multitasking among

multiple activity types and subtypes within a short time period.

In sum, we are left with the sense that the more closely the concept

of leisure is examined, the

more slippery it becomes. Although the considerations discussed above

are important, as a

pragmatic (if somewhat unsatisfying) solution to the general question

of defining leisure we may simply conclude, as US Supreme Court Justice

Potter Stewart said about pornography, that we may not know how to

define it, but we recognize it when we see it. Of course, empirical

studies of leisure will ordinarily need to be more specific than this,

and that can be accomplished by narrowing the definition for any particular

investigation in ways that will best fit the objectives of that study

(Samdahl, 1988).

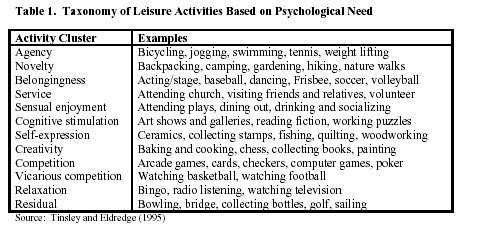

2.2 Previous Classifications of Leisure Activities

Classification systems related to leisure activities and travel can

be found in a number of

different contexts, including the literatures related to travel, activity

analysis, time use, and

leisure. Although there are some interesting taxonomies based on the

orientation of the individual toward leisure in general (Snir and

Harpaz, 2002); personal values, personality, and lifestyle (Madrigal,

1995; Lanzendorf, 2002); or the purchase of leisure activities (Reid

and Crompton, 1993), here we limit the discussion to studies that

classify leisure activities themselves, according to various dimensions.

At the simplest level, some typologies are based merely on the nature

of the activity. For example, for the purposes of avocational counseling

for the elderly, Overs, et al. (1977) classify activities under sports;

nature; art and music; organizations; education, entertainment, and

culture; volunteer; games; crafts; collecting. Passmore and French

(2001) offer a simple tripartite classification: achievement leisure

(playing sports, hobbies, creative and performance arts); social leisure

(activities for the purpose of being in the company of others); and

time-out leisure (listening to music, watching TV, contemplation).

Another relatively simple classification is based solely on purpose.

For example, the 2001

National Household Transportation Survey uses two categories of trip

purposes that could be

considered “leisure”: “social recreation” and

“eat meal.” The social recreation category comprises five

subcategories:

• go to gym/exercise/play sports,

• rest or relaxation/vacation,

• visit friends/relatives,

• go out/hang out (entertainment/theater/ sports event/go to

bar),

• visit public place (historical site/museum/park/library).

The eat meal category comprises two subcategories:

• get/eat meal and

• coffee/ice cream/snacks.

Other typologies involve objective characteristics of the activity

itself. For example, in addition to distinguishing social from recreational

purposes, Meurs and Kalfs (2000) consider the dimensions of :

• number of overnight stays (day trips, short

stays of 1-3 nights, short holidays of 3-5 nights

away, and long holidays of more than 5 nights away);

• trip length (short trips of up to two hours, and day journeys

of more than two hours);

• destination location type (local, regional, national, international);

and

• role of journey (purely to reach a destination, versus having

an intrinsic recreational value);

where the latter dimension of role is subjective rather than objective.

Bhat and Lockwood (2003) classify weekend out-of-home social/recreational

activities according to whether they are physically active or passive,

and whether they constitute travel itself (e.g. jogging, cycling)

or take place at a specific out-of-home location.

Several classifications of leisure activities are based primarily

or in part on individual values or psychological needs. For example,

Holmberg, et al. (1990) list 760 leisure activities classified by

combinations of two of the following six interest dimensions: realistic,

investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, conventional. Tinsley

and Eldredge (1995) developed a taxonomy of leisure activities based

on their psychological benefits. Starting with a list of 82 leisure

activities and an empirical rating of each leisure activity for eleven

different psychological benefits, they used cluster analysis to define

12 classes of leisure activities (Table 1). The psychological basis

of these classes is appealing in that it might provide a convenient

way of hypothesizing which kinds of leisure activities are more likely

to be impacted by ICT and in what ways. For example, agency activities

involve physical exertion that is not required for ICT-based activities.

Activities fulfilling the “novelty,” “belongingness,”

and “sensual enjoyment” needs also seem

unlikely candidates for substitution (the category 1 effect of ICT

discussed in Section 3.1 below).

For all of these activity classes, however, ICT may play an important

role in managing travel and may even generate travel (the category

4 effect). Activities fulfilling other needs, such as

cognitive simulation, self-expression, and creativity, do not so clearly

necessitate travel to begin with, in which case ICT may provide a

new dimension to the participation in these activities (the category

2 effect).

Continua >>>>>

4 Anable (2002, p. 181) comments that leisure “represents

one of the only journey purposes with essentially universal participation”,

and G`tz (2003) found that there was less variability across lifestyle

clusters in the time devoted to leisure activities than in the time

spent on non-leisure.

5 The exceptions are those maintenance activities that must be performed

directly on/by the individual herself, such as eating, personal grooming,

and medical appointments.

6 Again, there are exceptions: some leisure activities undertaken

out of duty to other people (see discussion below) may occasionally

be outsourced, as when we get someone to take our place at a social

or entertainment event we really do not wish to attend.

7 For similar views on the social-psychological fulfillment aspects

of work, see Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre (1989) and Tschan, et al.

(2004); see Lewis (2003) for a thoughtful and balanced discussion

of whether professional knowledge work is “the new leisure”.

For a divergent perspective, in which “exciting and strenuous”

leisure pursuits are chosen in deliberate contrast to “boring

and sedentary” jobs, see Kernan and Domzal (2000, p. 97).

8 It is perhaps not coincidental that all the examples just given

involve a location-based version of the activity rather than an ICT-based

version. It may well be that the leisure aspects of a mandatory or

maintenance activity are stronger in its location-based form, although

on-line shopping seems to have a strong leisure component.

9 For example, a high-stress occupation such as stockbroker may be

all of those things (much of the time) without being considered leisurely.

On the other hand, the opposite condition, relaxation, cannot be used

to define leisure, since many leisure activities such as those involving

strenuous physical exercise would not be considered relaxing.

10 Whether constantly being “on call” is a desirable condition

is of course debatable, and probably differently

desirable for different people. Our point is simply that it is a reality

for many people, with real implications for travel.

11 The boundary between this category and the preceding one is also

blurry, technically depending on whether the interspersed activity

fragments occur one at a time, or overlap. In practice it can be difficult

to make this distinction, depending in part on the time scale at which

activities are distinguished. A 10-minute Internet shopping episode

at work could be distinguished separately (constituting sequential

interleaving) if the time scale were in minutes, but would be considered

multitasking (a secondary activity overlapping the primary activity

of work) if the time scale were in hours.

|