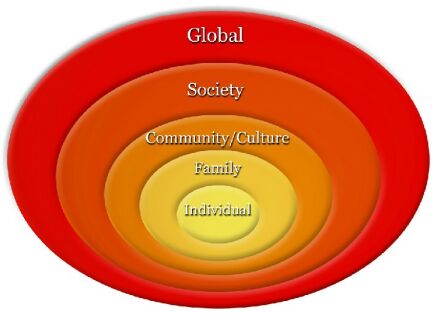

A second aspect of the model is that human beings do not develop in isolation; they develop in a variety of contexts -- environments which surround the individual human being and which he is in constant interaction play a major role in development (e.g., Bridge, Judd & Moock, 1979; Bronfenbrenner, 1977, 1979, 1989)

The first level of the ecology or the context of human development is the microsystem. This level has the most immediate and earliest influences is the family,

along with local neighborhood or community institutions such as the school, religious institutions and peer groups as well as the specific culture with which the family identifies.

The second level is the mesosystem. This has an intermediate level of influences such as social institutions involved in such activities as transportation, entertainment, news organizations, and the like. The influence of these systems and institutions is filtered through the microsystem institutions.

The third level is the macrosystem. This is the most removed influences such as international region or global changes. For example, the movement from the agriculture and industrial economies to an information-age, global economy is having widespread influence on the ways societies, communities, and families are operating.

While we sometimes tend to focus on family or school influences on human development, we should always remember that there are other important influences. An African, as well as Native American, tradition states that it takes a whole community to raise a child.

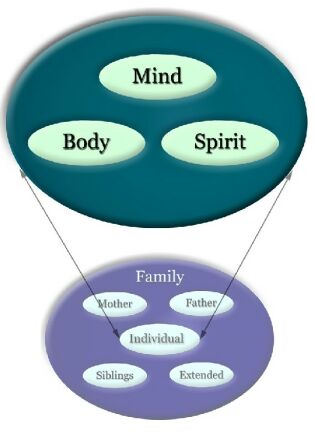

An important aspect of this model is that it reflects an approach that defines human beings as having both biological and spiritual components of their nature (e.g., Danesh, 1994; Frankl, 1946/1984). From the perspective of philosophy, this is called a dualist position. That is, it is assumed that the biological brain and the psychological mind are two separate entities and can be studied separately. It is also postulated that human beings have a soul or spirit that influences the operation of the mind and that continues to exist after the decomposition of the body. The opposite of this position, the materialistic viewpoint, states that there is no non-materialistic aspect to the universe and to human beings and that the mind is totally a result of brain functioning. From this perspective the mind ceases to function when the brain ceases to function.

On of the implications of the dualist position is that there are a variety of sources of knowledge about human beings and human nature. That is, if human beings are more than what the materialists believe, then science, which is limited in its study to the material universe, cannot inform us totally about human behavior. If we are to have a more complete understanding we must look to additional sources of information. While an attempt has been made to stay within the parameters of a scientific approach as the standard for developing understanding and discerning truth, I acknowledge that other sources of knowledge (e.g., personal experience and intuition, spiritual and religious scriptures and background, and study of philosophy) have also influenced the development of this model and my interpretation of data. I will make my viewpoint about human beings as explicit as possible so that you can accurately judge to what extent my philosophical position may force a particular interpretation when another is equally valid.

Throughout the course there will likely be instances where the research findings presented in class do not match knowledge you have acquired through other sources. It is also possible that you have a different viewpoint or philosophy that would allow a different interpretation of data than the one I have given. Should this occur you have every right to bring in additional data or to interpret data in a different way than that provided in the text or in a class presentation. In these instances, please state your viewpoint or your additional data as clearly and as concisely as possible, explaining how your interpretation or data is just as valid, if not more so, than that previously given. View these times of dissonance as opportunities to develop new understandings or to integrate previous understandings in new ways. It is not always necessary to completely discard knowledge derived from either science or other sources, but interpretations may need to be modified in order to include the findings derived from science. I encourage others to develop their own models that might highlight other aspects of human behavior that do not receive adequate attention in this model.

References: