|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

1. Incomes in the United States have been getting more unequal since the late 1970s.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

If Bill Gates and I started our own country in which we were the only residents -- call it Gatesbergia -- it would be racked by the worst income inequality in the world. The "haves" of the society would make hundreds of thousands of times more than the "have nots…" And if Warren Buffet, the Sultan of Brunei and Rupert Murdoch immigrated to Gatesbergia, the problem would be even worse, for the gap would get wider and I would be "left behind." –Jonah Goldberg

|

For most middle-to-low-income families, the economic gains of the past 25 years have been modest. Even so, they have been achieved, on average, with more combined hours of work.

|

|

What are your chances of reaching the… |

||

|

With parents in the… |

Bottom quintile |

Middle quintile |

Top quintile |

|

Top income quintile |

6.3 % |

16.3 % |

42.3 % |

|

Middle income quintile |

17.3 % |

25 % |

15.3 % |

|

Bottom income quintile |

37.3 % |

18.4 % |

7.3 % |

Those who lament the rise in inequality are often dismissed as economically

naïve. They are faulted for forgetting that this is a country where, in

the words of one scornful commentator, “people simply do not remain in

the same top and bottom income categories over time.”

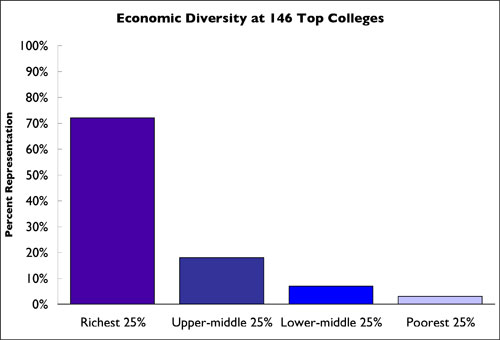

In fact, many people do. The U.S. is not only more unequal than it was (and more unequal than other countries), but less economically mobile than many have assumed. Recent estimates of inter-generational mobility are sharply lower than the consensus of two decades ago. Some researchers see evidence that mobility itself has declined, because of a proliferation of dead-end jobs and a labor market sharply divided between those who possess, and those who lack, a four-year college degree. That all-important credential, in turn, appears to have become less accessible to the children of parents who are neither wealthy nor well-educated themselves.

The immigrant success story is another economic legend that may due for reexamination. The gulf between immigrant and native-born incomes is roughly three times wider today than it was a century ago, according to the Harvard University sociologist Christopher Jencks.

"If

you come here as an adult,” Jencks’ economist colleague George J. Borjas

explains, “it's very hard to get more education, which is the only way

to get ahead today."

Source: Anthony B. Carnevale and Stephen J. Rose, Race/ethnicity and Selective College Admissions, in Richard D. Kahlenberg, ed., America’s Untapped Resource: Low-Income Students in Higher Education (Century Foundation, 2004)

America has “an economy that is slowly stratifying along class lines,” Aaron Bernstein wrote in Business Week. “Upward mobility is determined increasingly by a college degree that's attainable mostly by those whose parents already have money or education.”

To speak with alarm about the gulf between rich and poor (or between rich and middle; or middle and upper-middle) is to invite the charge of fomenting “class warfare.” Indeed, the question of inequality has rarely stirred much passion in America except in periods of deep discontent, and it has usually been framed as a problem of “haves” and “have-nots” or (in recent years also) “have lesses.”

These laments arise out of feelings about justice, suffering, and mutual obligation that are as old as humanity, and deserve respect rather than scorn. It is only by making a religion of the “free market” that anyone could possibly construct a reasonable-seeming justification for American-style differences in earning-power between, say, a janitor and an investment banker. But the poor are not the only victims of inequality, and the damage is not to be measured solely in material terms.

In the U.S., perhaps more than in any other prosperous society, inequality reaches into dimensions of life where most people would prefer to believe that money does not rule. The service someone receives from our education and health-care systems, to mention two large cases in point, is profoundly dependent on money and class. The economic givens of early childhood are frighteningly good predictors, in fact, not only of access to health care and formal schooling, but of lifelong health and educational attainment.

Americans’ experience with the political process is also dramatically affected by their place on the socioeconomic ladder, and here, too, the influence runs both ways. Inequality shapes the system, and the system aggravates and perpetuates inequality.

These multi-dimensional effects and feedback loops are important for what they reveal about the nature, severity, and scope of economic inequality in America. In addition, they underscore the issue’s relevance to those focused on more policy-specific problems. Your first concern may be education, health, poverty, racial justice, the workplace, the environment, or the preservation of democratic government and a strong civil society. In all these realms, recent history has taught us that the fulfillment of broadly shared ideals is going to be immensely difficult in a world of highly concentrated wealth, income, and economic power.